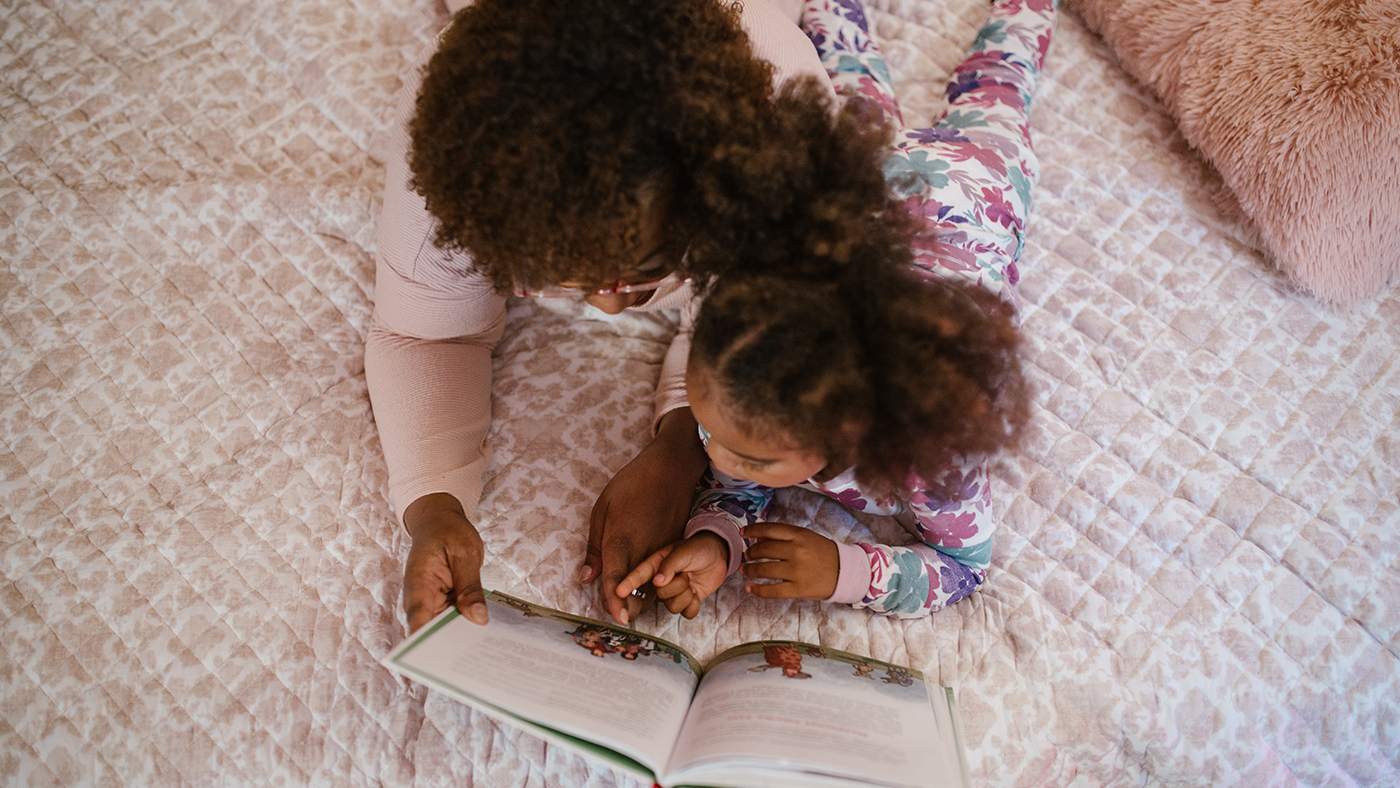

Sharing books with your child

- Reading,

- Books

Why is reading important?

Reading with children is a wonderful experience, and it is during these early years that children can develop a lifelong love of books.. When we read with our children as parents or family members, we can pass on huge amounts of enthusiasm about reading. Picture books are an excellent way to introduce children to reading; plot and subplot, goodies and baddies, mysteries to be solved and guessed at, heroes on missions, compassion, achievement, intrigue, resolution, and much more may all be found in picture books.

Frank Smith, a literacy theorist once wrote, “Children probably begin to read from the moment they become aware of print in any meaningful way… the roots of reading are discernible whenever children strive to make sense of print before they are able to recognise many of the actual words.”[1]

This is a lovely quote since the love of reading usually begins with a spark of curiosity, and for reading to be enjoyable, a child must be interested in what they are reading. Children have access to reading in a variety of forms and if a child recognises a toy logo, book cover or a juice carton, they have fundamentally learned to read at the simplest level. When we think of reading, we think of books, but your child is now at an age where they could be interested in magazines, toy catalogues, or instructions on how to assemble a new toy.

Any experience with reading is fantastic; we wish forchildren to be captivated by print and to be able to connect it to meaning. Reading a physical book adds value to the experience and can inspire a passion for reading. The exquisite feel of the book in their hands, their expressions of awe or joy when they select a favourite book, and the fact that they can now handle it, open it, and turn the pages without adult support. How exciting must this feel for a child?

Your child's pre-reading skills will have benefited greatly from all the books you have read together. They have had tremendous opportunity to learn from books by expanding their worldview, general knowledge, cognitive skills, and social awareness.[2] They are now ready to take the next step toward reading independence.

Let me read to you

It is around now that your child may be ‘reading’ to themselves and telling you what the illustrations or some of the words say. Researchers have found that children start to memorise favourite stories which helps them to retell the story, possibly using character voices and intonation.[3] This type of reading is invaluable, as it is teaching your child some of the basic universal elements of storytelling and reading such as setting, character and structure. They will later understand more about responses, consequences and reactions when reading and telling stories. Learning these skills now has been linked to later competent literacy development.[4]

It could be that your child may now understand that in English, print is read from left to right, top to bottom, and front to back. Even if they don't follow the rules to the letter, the fact that they open the book to the first page and turn the pages from there shows they understand the basic concept of reading.

Identifying letters and decoding print

As your child’s skills in reading become more confident, you may notice that they begin to recognise some letters and words in the print of storybooks. They could be eager to try 'reading' independently and are no longer relying exclusively on their memories. This phase of learning can take a long time. Break it down into smaller parts if your child is showing signs of wanting to read, and share the reading of the books. Invite your child to read one line, while you read two pages. Provide hints within the illustrations to help them decode words or invite them to sound out the initial letter then look for a matching illustration to assist them in their search. Many research studies conclude that if a child is supported to look for familiar letters and words within text, it will help them understand the context and meaning of the print.[4]

Comprehension, fluency and vocabulary

When children are exposed to a wide variety of books, it is said to boost an enormous amount of learning. Lots of rich new language can be introduced, opening up times for discussion as to what this new vocabulary means. You may notice your child demonstrating comprehension skills by asking questions or wondering about suggestions you have offered about the story. Many research studies have found strong evidence to suggest that when children are introduced to words and they have time to think about what the word means, they can more easily provide a definition for the words from then on.[5] Once the skills of decoding and understanding text are in place, this provides a secure foundation for reading to take place.

Social and emotional

Storybooks can be tremendous at helping us explore the idea of relationships. In many books we will find adults comforting children, or getting the wrong end of the stick, animals and toys get lost or face huge ordeals! Sharing these together can open up so many moments of talk between children and adults.

They are also great at supporting experiences that may be happening at home and offering ideas to try to help children explain their feelings. When asked about feelings, your child may be able to tell you that a character was feeling, for example, sad, and tell you why. They have enough knowledge of their own world to try make sense of what they are reading and they can apply a response knowing that they are applying what they know to the character.[6]

Cognitive understanding

Your child is at a perfect age to start questioning what they see and read about in stories. In books, there are many different concepts presented; some are realistic, while others entertain a broad range of imagination. Many children's stories feature animals, and in some, the animals talk and wear clothes. Because your child has a better understanding of their world, you might be able to wonder together if an animal would wear clothes. 6] It is thought that their brain has developed to the point that they can now think critically about size, scale, and proportion, as well as question whether certain elements of stories might actually occur.[6]Your child may now be at the age where they can remember a whole story. If you try to rush through a book and miss a section, you will no longer be able to get away with it. Your child's cognitive and memory abilities have reached a point where they can inform you when the story is not as it should be.

Reading and storytelling

Books can become much longer in length now that your child is at this age. When stories are being read and shared, so many concepts can be introduced and the open discussions that can take place are endless. Their imaginations can be taken to new levels and this opens up new lines of inquiry, wonder and amazement. Your child may become completely involved in some stories, so much so, they may act out with toys after the story has been read.

It’s a great moment when you hear your child starting to re-tell wonderful stories that have a flow and a theme. They are actively bringing a book to life and engaging in their own dramatic show. It is at this stage where tenses start to appear in their storytelling and they can sequence events into an order that is starting to make sense.[3]

What can we do together at home?

What an enchanting time it is now for your child on their reading journey. There are so many wonderful activities you can share together that will harness their new ability in understanding the concepts of books and reading. Here are a few ideas you could try out at home:

- It is pretty likely your child will still absolutely love anything that is about themselves. You could write a story together and your child could draw some illustrations and potentially write some of the letters or words. Encourage them to think about the story structure, characters and setting.

- Using illustrations and drawings in writing is a skill that dates back thousands of years. You could show your child some of the cave images of animals drawn when different groups of people communicated with others. Maybe your child could create a cave drawing of something that has happened that day.

- Read yourself. If your child sees you engaged in reading, they are more likely to pick up a book themselves.

- Make a bookshelf. Having books presented so that they are easy to reach and see offers an immediate opportunity to access a book.

- Set up a book club. Set aside a time each week and share a book together. Once you have read the book, review it, discussing what happened and ask if your child thinks they would have changed it in anyway, or how they felt about the story.

- Make up a story, stories do not need to come from a book. Children enjoy listening to you make up stories. They can be about anything, for example, things you did as a child or things your child did when they were a baby. Children love to hear about themselves and listening to stories about their own lives is bound to capture their attention

- Read in a den. The excitement of reading in a different place can be amazing. Take in a torch or a lamp and read under the covers, in a den or any dark space you can create.

Keep on trying when reading. It is a skill that will take time but most things in life take time to accomplish successfully. Brian Anderson, an American magician, advises children to try something for 10 minutes a day, each time you will get a little better.[7] Help them out by encouraging them to run their fingers along the text and identify words or letters you know that are capable of. Make it tricker as you see fit.

One of the amazing aspects of sharing books with children is that reading may take place at any time and in any location. It doesn't have to be scheduled, or it could be a regular part of your day. However and whenever your child is read to, they are benefitting from an emotionally engaging moment with a very loved person. Sharing a book creates precious moments and times to be cherished.

References:

[1] A. Anbar (2004). The Secret of Natural Readers: How Preschool Children Learn to Read. Greenwood Publishing Group

[2] P.A. Ganea, L. Ma, J.S DeLoache, (2011). Article: Young Children’s Learning and Transfer of Biological Information from Picture Books to Real Animals. Child Development, September⁄ October 2011, Volume 82, Number 5, Pages 1421–1433

[3] Sample Gosse, H., & Lovell, M., (2008). Caregiver Narrative: Prereading Development 49 - 60 Months. In L.M. Phillips (Ed.), Handbook of language and literacy development: A Roadmap from 0 - 60 Months. [online], pp. 1 - 9. London, ON: Canadian Language and Literacy Research Network. Available at: Handbook of language and literacy development

[4] A. Van Kleeck, S.A. Stahl, E.B. Bauer (2003). On Reading Books to Children Parents and Teachers Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

[5] Sample Gosse, H. & Lovell, M. (2008). Caregiver Narrative: Prereading Development 37-48 Months. In L.M. Phillips (Ed.), Handbook of language and literacy development: A Roadmap from 0 - 60 Months. [online], pp. 1 - 9. London, ON: Canadian Language and Literacy Research Network. Available at: Handbook of language and literacy development

[6] M. Nikolajeva (2014). Reading for Learning. Cognitive Approaches to Children’s Literature . John Benjamins Publishing Company

[7] B. Anderson (2021) Blog: The Magic of Self Confidence. Available online at: The Magic of Self-Confidence | RIF.org